Sources Presented

Takeda Shingen and The Takeda Clan

(An introduction to the various sources – old and present)

I intend in the following pages to present some of what is “out there” regarding sources on the Takeda clan of Kai province (today; Yamanashi prefecture). Quite the opposite to certain popular and present notions; “that there is nothing left”; in fact, there are quite a lot of sources still around on the Takeda; letters, diaries, temple chronologies, death registers and of course war tales. During the 16th century and before, the Takeda communicated with countless of other clans and individual samurai, Buddhist monks, Shinto priests and traders and craftsmen throughout the Japanese islands. So of course, there are still in existence letters and information related to the Takeda at places far from the Takeda’s clan’s homeland (Yamanashi prefecture).

Within the above sources many of these are written during the Edo period (1603-1868), but a lot are contemporary sources, especially on old letters (komonjo) are still to be found. A large number are transcribed and exists only within these later books, but that doesn’t discredit them as fakes. It is quite understandable if letters from the 16th century are of poor quality, water damaged, or by fire, and even eaten by insects; a special kind of insects love Japanese paper, and probably thousands of original letters have been “eaten” by them through the centuries. I got some Edo period books with traces of these “evil” insects’ gobbling feast. Professor Owada at Shizuoka university told me that there are forgeries around when it comes to old letters, but they seem to have a pretty good knowledge of these in the academic world.

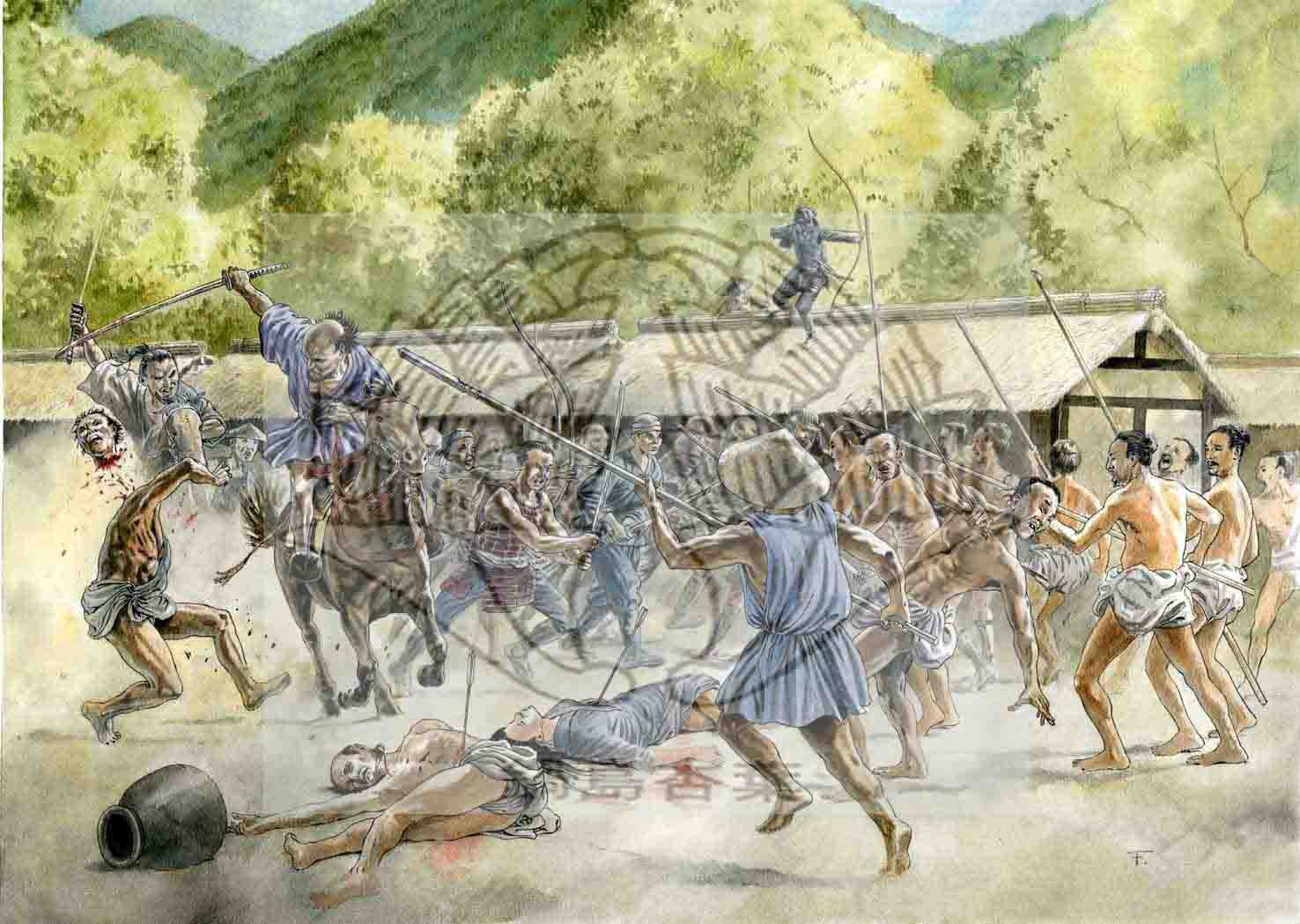

During the invasion of Kai province in March of 1582, many fortresses, temples and manors were destroyed (Oda’s total war on the Takeda), and of course one must assume that a lot of various contemporary documents and other writings were destroyed during these turbulent weeks. One temple was actually saved by direct order from Oda Nobunaga, the original letter exists, and it is addressed to the Suwa jinja in Suwa district of Nagano (Shinano) prefecture. It is a so-called kinsei letter (decree of rules), telling his soldiers to leave this temple in peace; no pillaging or destruction allowed. But although this example seems to be an exception during this invasion, a lot was saved by hiding it from enemy troops. Several temples and Shrines hid away many of their valuable possessions before the enemy entered their premises. Many monks and priests fled the area and hid among the hills and valleys until it was safe to reappear, and they hid items of value at locations only they knew of. One must remember that the invading Oda and Tokugawa army were in unfamiliar territory.

One such example is the Unpôji temple located several kilometers up in the hills above Enzan town in Yamanashi prefecture. Today they got in their possession several original flags and other artefacts which once belonged to the Takeda clan. The monk, which was there when I visited the temple about 25 years ago, told me that fleeing soldiers handed these artefacts over to the temple for safekeeping during the turbulent spring of 1582. Hundreds of temples and Shrines experienced the same and it was not unusual that a samurai clan’s temple was trusted with safekeeping family treasures – such as documents and various artefacts. It was much safer to hide it at a temple than at the castle or manor belonging to a samurai; his property would certainly be the target under an invasion.

One other good example of a contemporary source is the diary (Ietada nikki) written by Matsudaira Ietada (1555-1600). Ietada was a vassal of Tokugawa Ieyasu. He took part in the various wars and campaign in 1582 against the Takeda. His diary is one of the greatest contemporary sources within the provinces of Mikawa, Tôtômi, Suruga and Kai. It might have been longer that what remains of it, but the diary begins with the year 1577 and follows through to August 1594. Ietada was killed at the battle of Fushimi Castle in 1600.

Sadly though, typhoons, earthquakes, fires, and wars have claimed a lot of precious artefacts and documents since the 16th century and up to present times, and quite a lot were lost during the bombing raids on Japan’s cities during WW2. There were a lot of private artifacts still within former samurais’ houses, and many of these were destroyed by bombs and the ensuing fires. Even so, quite a lot remain, and in various official and private collections there are several thousands of old documents in existence. One such example of “still around” is the collection of documents and artefacts in the possession of Yoda Takekatsu in Nagano prefecture. I met Takekatsu, who is a descendant of Yoda Masatomo (Aiki Ichibee) in Saku district. I bought a book that he had published; it dealt with “Yoda Masatomo and Takeda Shingen – a family history”.

This nice old samurai had quite a lot of documents still at his house, and he had written a beautiful historical book; sadly, this book is not available in main stream bookstores in Japan.

A series of publications; “Sengoku ibun Takeda-shi hen dai ikkan” (Takeda clan’s documents volume 1) was published by Tôkyôdô shuppan (between 2002 and 2006), and the complete 6 volume set contains over 4000 letters from the Takeda clan and their vassal families. Spanning over five centuries these 6 volumes are indispensable when it comes to the history of the Takeda clan. These volumes are located at the Yamanashi prefectural library, about one hundred meters from Kôfu train station. In addition, the library contains a few hundred other books, which most of them are written post WW2 – a true treasure hole of literature on the Takeda clan.

In addition to these contemporary letters, there are hundreds of war chronicles, registers and records, diaries and so on. Not all of these are trustworthy when one considers their content, but all in all they have some historical value, but it takes time to do serious work using all these available sources. Regrettably, too many discards later sources without even doing serious research before they judge these later sources. Later sources, I mean, literature composed during the Edo period. Many such were written by various clan members – honoring their forefathers’ exploits during the Sengoku period and before. In fact, all the daimyô under the Tokugawa shogunate were ordered to write down their family history. Certainly, some of these family records include exaggerations and probably false information, but still, one must do serious research and keep an open mind, but at the same time maintain a critical approach to its contents. Compare sources and verify “war-tales” using contemporary letters, if there are any. In order to be able to reconstruct the complete and correct picture, archeological work is also an indispensable addition to the written sources.

There are some Edo period works of literature and collections of writings that are based on 16th century sources, but due to natural and man-made calamities mentioned above, many of these letters and other writings have been destroyed; so, the only remaining written accounts or second-hand sources still in existence are these from the Edo period. but that doesn’t automatically make them fabricated writings, they might contain valuable information on past events and persons; this needs to be seriously researched, but as I mentioned above – this work is time-consuming.

Just to add one more interesting piece of information: In 1576, Katsuyori ordered various artefacts after his father, Shingen, to be sent to Koyasan Mountain in Wakayama prefecture . This was done in relation to the three-year-secret of his father’s death. Three years have passed, and a formal funeral ceremony for Shingen was held in Kôfu. A letter at Koyasan verifies this information.

REGARDING THE TAKEDA AND POST-WAR HISTORIANS AND WRITERS

(Comming later)