Ieyasu and the Unification of Mikawa

Tokugawa Ieyasu and The Unification of Mikawa (1560-1566)

Mikawa Province and its’ neighbors

The Province of Mikawa flows like a great cape out and down from the mountainous north, mainly Shinano province, and all the way down to the Bay of Mikawa. Large flat areas with a few long and wide valleys, carved out from the mountains through the ages. The province has huge areas ideal for various agriculture and of course rice-fields. The Mikawa province itself borders to the provinces of Owari in the west (the Oda clan), Mino in the northwest (the Saitô clan), Shinano to the northeast (the Takeda clan), and Tôtômi in the east (the Imagawa clan). There are several rivers within the province forming natural borders, and supplies the area with the necessary water for all life and vegetation to thrive. The main river in the vest is called Sakai, and this river forms the borderline between the Mikawa and Owari provinces. In the east there is no natural river that forms the border, instead it is a small mountain range running all the way from Shinano province in the north down towards the coast, and it bends around the vest side of Lake Hamana before it ends up in the Bay of Mikawa. Located in the middle of the eastern part of Mikawa there are two rivers, the Yahagi and Sugou, where the main river is the Yahagi and the other is a tributary river. At almost the exact point where the two rivers join, the castle of Okazaki is located, on a small plateau. The castle was built by Saigô Tsuguyori in around 1455, but during the turn of the century it was attacked and taken over by the Matsudaira clan.

Imagawa Yoshimoto – April 1560, the main part of Mikawa is under the control of Imagawa Yoshimoto (1519-1560), the ruler of Suruga and Tôtômi provinces. One of the major clans that are under their banner is the Okazaki Matsudaira clan. There are several branches of Matsudaira, in fact 14 in all, and they are all at this moment in time under Imagawa influence and leadership. Not by a strong sense of loyalty, but rather forced into a vassal/master bond after the Imagawa invasions during the last decades. Yoshimoto was an aggressive and eager conqueror, but this constant victorious streak can lead to a sudden downfall, and in the province of Owari he would soon meet his match.

On the evening of the 19th of Mai 1560, Yoshimoto met his end at the battle of Okehazama in Owari province. One of his vassals in this battle was a young samurai under the name of Matsudaira Motoyasu – later better known to all as Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). Ieyasu was only 18 years old at this time in history, but even though without many years on his back he would surely show a great talent for military strategy and in the arts of war. In the battle at Okehazama it was Oda Nobunaga (1534.1582) that triumphed and once and for all had hampered the Imagawa clan’s ambitions of expansion towards the west, or in any other direction for that matter. The heir to the house of Imagawa was Yoshimoto’s son, Ujizane (1538-1614), only 22 years at this time. He was now left with the managing of three provinces – all in the danger of falling into military chaos. It would be imperative for him to safeguard and protect his domains before the grip that the Imagawa had on the provinces would fade.

One of the many clans that wanted to break away from the master/vassal relationship with the Imagawa was the Matsudaira clan, and it came in the shape of Ieyasu – who ruled the Okazaki Matsudaira clan. Actually, he took over the clan already in 1549 when his father was murdered by a retainer, but at that time Ieyasu was just a young boy and a hostage with the Imagawa at their fortified mansion in Sunpu. During the years under the Imagawa the young boy would receive a more unrestrained role and instead of being a hostage himself, he would now place other family members there to make his master content.

After the defeat at Okehazama on the 19th of May Ieyasu held up at Ôdaka fortress, but as soon as the information reached him on his master’s demise, he set off at once for his home province. On the 20th he reached Daijûji temple in Kamoda, located to the north of Okazaki Castle. Here Ieyasu decided to wait out the Imagawa soldiers that were stationed there. At the time of his father’s death, in 1549, the castle of Okazaki came more or less under direct Imagawa control, and it seems that almost on a permanent basis it was a base for Imagawa soldiers on duty in Mikawa. So when the news of their lord’s death reached the garrison at Okazaki, they set out at once for their own territories. This was exactly what Ieyasu had waited for, and when the coast was clear he set out for Okazaki and on the 23rd of May he was back at his castle.

The Fight for Independence

Now it was important for him to consolidate his position and make sure that the Matsudaira clans would be united in the coming months and years in Mikawa. There would certainly be a period now where the provinces of Mikawa, Tôtômi and Suruga might fall into military chaos and subsequently social unrest. Ieyasu seemed to have waited for such an opportunity like this, for his innermost desire seems to have been for a long time, to break away from the Imagawa claws. But in order to do this successfully he would need to be quite clever. The reason for this was that in Sunpu his family was held hostage, and if Ieyasu was to publicly break with the Imagawa, his family members held in Sunpu would certainly be put to death. Ieyasu and the Matsudaira clans were not the only ones that wanted their freedom back, many large and small families wanted to exploit this moment, but Imagawa Ujizane would not let his father’s winnings fall that easy.

Ieyasu was now at his Okazaki Castle and soon after the battle of Okehazama he continued to attack fortresses and castles that belonged to the Oda clan of Owari. Mainly castles along the border between the two provinces, the Sakai River, were targeted. But it seems that during this time he had, in the back of his mind, other goals and ambitions for the clan’s future, and quite soon his targets shifted to the east. Ieyasu wanted to expel the Imagawa and unite Mikawa under his banner – a war with his patronage family was at hand.

Ujizane found himself in a right out difficult situation, he had two alternatives, he could give up Mikawa and concentrate on keeping Tôtômi and Suruga, or he could put up a fight for his father’s holdings. Ujizane decided for the latter. Evidence for this policy can be found in several letters issued by Ujizane throughout the 1560s to various families in Mikawa and the border areas of Tôtômi province. These letters of recognition on military exploits have great value for the supposed policy that Ujizane wanted to fight for Mikawa. At the same time as the letters contains recognition of bravery, they also refer to battles within the province during this period, and thereby gives us solid evidence for the assumption above.

Soon after the battle at Okehazama Ieyasu wanted to end the lord/vassal relationship with the Imagawa, and evidence for such a hasty exit can be found in a letter addressed to Imagawa Kazusa no kami (Ujizane), it is dated 20. January 1561, and it is signed by the Shôgun, Ashikaga Yoshiteru (1536-1565). In the letter Yoshiteru is requesting, or demanding, that there must be an end to the hostilities between the Okazaki Matsudaira (Ieyasu) and the Imagawa clan. The present situation makes it impossible to commute between the Kantô area and the western part along the Tôkaidô road. A warfare state makes it unsafe for travelers to use the Tôkaidô road, and this cannot continue. So, from this letter’s contents it is clear that hostilities have broken out within the Mikawa province, and the whole area is unsafe to travel through. No more than seven months have passed and Ieyasu is on the warpath aimed at his former lord.

Ieyasu had no intentions of making peace with the Imagawa as long as they remained within Mikawa – The letter sent by Yoshiteru had no effect on the two combatants, and the war continued. At the same time as Ieyasu made war with the Imagawa, he also waged war with the Oda clan to the vest. But it is now that destiny comes into play, as far as Ieyasu goes. Mizuno Nobumoto (?-1575) was an older brother to Ieyasu’s mother, thereby making him an uncle of Ieyasu. Mizuno, lord of Kariya Castle located at the border between Mikawa and Owari, had broken away from the Imagawa several years ago, joining the Oda clan instead, and by doing so the Imagawa turned their hatred towards Ieyasu’s mother. Ieyasu would not be permitted to meet his mother again, and the young samurai came to be separated from her from the age of three to he was a young man of more than twenty years old.

This was the cruel reality for a samurai-child during the Sengoku Jidai (1467-1615), used as a political and strategically piece in a complex struggle for power. Ieyasu got used to his life without his mother. There might be a chance now – he thought, as he waged war on his former patronage family. The early spring of 1561 turned the whole war in Ieyasu’s favor. The whole northeastern part of Mikawa broke off their relations with Ujizane and joined Ieyasu. This was a huge blow to the Imagawa’s grip and holdings in Mikawa, and now only a few scattered castles in the southern part of the province remained loyal. Among those who turned their coat we find; Matsudaira Iehiro on Katahara Castle, Matsudaira Kiyoyoshi on Takenoya, Saigô Masakatsu on Gohonmatsu, Suganuma Sadakatsu on Inomichi, Suganuma Sadamitsu on Noda, Suganuma Sadatada on Damine, Suganuma Masasada on Nagashino, Okudaira Sadayoshi on Tsukude and Shitara Sadamichi on Kawaji.

This massive breakoff did not go unpunished, and not long after several of the family members of the lords that had turned their back at the Imagawa got their loved-ones executed. One of these unfortunate lords was Matsudaira Iehiro. His youngest son, Ukon, was a hostage at Yoshida Castle in Mikawa, and together with family members from the Okudaira, Suganuma, Okuyama, Mizuno, Shinoda, Ôtake, Shiroi and Asaba were all taken to the Ryûnenji temple, located in the vicinity of the foot of the castle, and executed. This awful act was done in the early spring of 1561. Breaching a contract of loyalty had its price, and as seen in this case many of the families were ready to pay this high level of family grief for the clan’s future self-determination and independence.

So this spring-revolution turned into a great opportunity for Ieyasu, and the fight for independence certainly got the necessary energy with this eastern boost in support – and not to forget, in pure military strength. Ieyasu continued now his campaign against the Imagawa bastions in the southern part of the province. Among those castles still remaining under Imagawa influence at the beginning of summer in 1561 was Kaminogô, Nishinogôri, Ushikubo, Yoshida, Tahara and Nishio, but there might have been others, less known. Within this southern part of Mikawa there were hundreds of smaller fortresses and fortified mansions during the 16th century. Although there might have been others, it was a severe blow to the Imagawa influence, and their grip on Mikawa, when the whole northeastern part of the province turned their coat. Isolating many of those still loyal to the Imagawa – so one should think that now it will be an easy task to overrun the remaining scattered oppositions. But this was not the case, time and time again Ujizane sent his soldiers over the border from Tôtômi to attack enemy positions. And not to forget, some of these remaining loyal castle-lords could yet enforce their will within their territories, and raise a force when needed. Ieyasu still had some hard fighting to conduct before his unification could be ascertained.

The autumn of 1561 would bring a lot of new thoughts and possibilities for Ieyasu. In September this year Ieyasu’s captain Honda Hirotaka attacked Tôjô Castle, owned by Kira Yoshiaki, and this was certainly one of the main bastions in southern Mikawa, and therefore it was an important catch. These military victories were of course of great importance to Ieyasu, but the greatest victory came later this year – it was the negotiations with Oda in Owari, which came about due to the previously mentioned Mizuno Nobumoto. He told Ieyasu that he could meddle between Ieyasu and Oda Nobunaga, and maybe there could be a long term peace between the two houses. This was certainly something that Ieyasu wanted to exploit to the full extent. A long-lasting peace with his enemy in the vest would be a great opportunity for him to at last unite Mikawa without fearing for his western flank. In the beginning talks, in form of letters, were conducted and Mizuno played a huge part in the final arrangement of a meeting between the two. On the 15th of January 1562 Ieyasu visited Oda Nobunaga in his castle at Kiyosu. An agreement was signed by the two parties and all the military hostilities came to a close – in fact it is recorded in sources that a so-called ceasefire came about already in February or March of 1561. This means that quite early there seem to have been some sort of correspondence between the two clans.

Ieyasu must have felt a great relief as this huge burden had fallen from his shoulders as he turned his horse towards Okazaki, but soon a worrying thought came to his mind. His wife (Tsukiyama) and two children (Kamehime and Nobuyasu) were hostages at Sunpu, and as soon as the news of his agreement with Oda would be publicly known, his family members would certainly be put to the sword. Ieyasu feared the worst, and he needed to act fast and quickly acquire something he could negotiate or bargain with. Who came up with the idea is uncertain, but it turned out that the lord of Nishinogôri Castle, Udono Nagateru, had two sons, and maybe Ieyasu could capture these two boys and get some kind of a deal with Ujizane. Nishinogôri Castle was located not that fare to the southwest of Okazaki, but time was short. On the 4th of February 1562 soldiers under the command of Hisamatsu Toshikatsu and Matsui Tadatsugu attacked Nishinogôri and the castle was overrun. The two boys, Ujinaga and Ujitsugu, were captured alive, but their father died in the fighting. The two boys were treated well and brought to Okazaki. Now, Ieyasu had finally got what he needed to strike a deal. The boys were actually cousins of Ujizane, and that is why Ieyasu thought that they had some value to the Imagawa. Ieyasu made contact with Sunpu and Ishikawa Kazumasa was sent off to make the exchange – everything went according to plan. This was a great personal success for Ieyasu, and soon there was a wholehearted reunion between father, wife and children at Okazaki Castle. In later records it is stated that Ujizane had to have been an utter idiot for going along with this exchange. The true reason on why Ujizane actually traded away these aces of cards for much less will, probably, never be truly known.

Finally an exhausting period was over for Ieyasu, and at last he could lower his shoulders and concentrate all his efforts on his goal of a unified Mikawa. So in the early spring of 1562 he worked on consolidating his position within the province and made sure that any invasion from the east would be met quickly and hard. All castles in the border area were strengthened, and this was certainly implemented by the lords on the border – they feared that their former lord wanted to punish them even further. This was legitimate fear, due to the fact that Ujizane tried to make an effort to gain back the lost areas, but not seemingly overeager at this moment. Maybe he had enough trying to hold on to the remaining provinces of Suruga and Tôtômi. The year ended with a few military confrontations but no definitive battle. In the beginning of 1563 Ieyasu was stronger than ever, and in March his very young son, Nobuyasu, was engaged to Oda Nobunaga’s daughter, Gotoku. This was of course a political arrangement, but still it was an important move for both of them. Now they could engage in other areas, on military matters, knowing that their back was secure.

On the 6th of July 1563 Matsudaira Motoyasu changed his name officially to Matsudaira Ieyasu (the last letter, in existence, with the name Motoyasu was sent out in June and addressed to Matsudaira Naokatsu, lord of Ôno Castle in Mikawa). It has to be mentioned that some other sources states another year on when he changed his name, but several letters from June 1563 goes a long way in verifying that it did not happened at least before that month in 1563.

Ikkô Ikki Rebellion

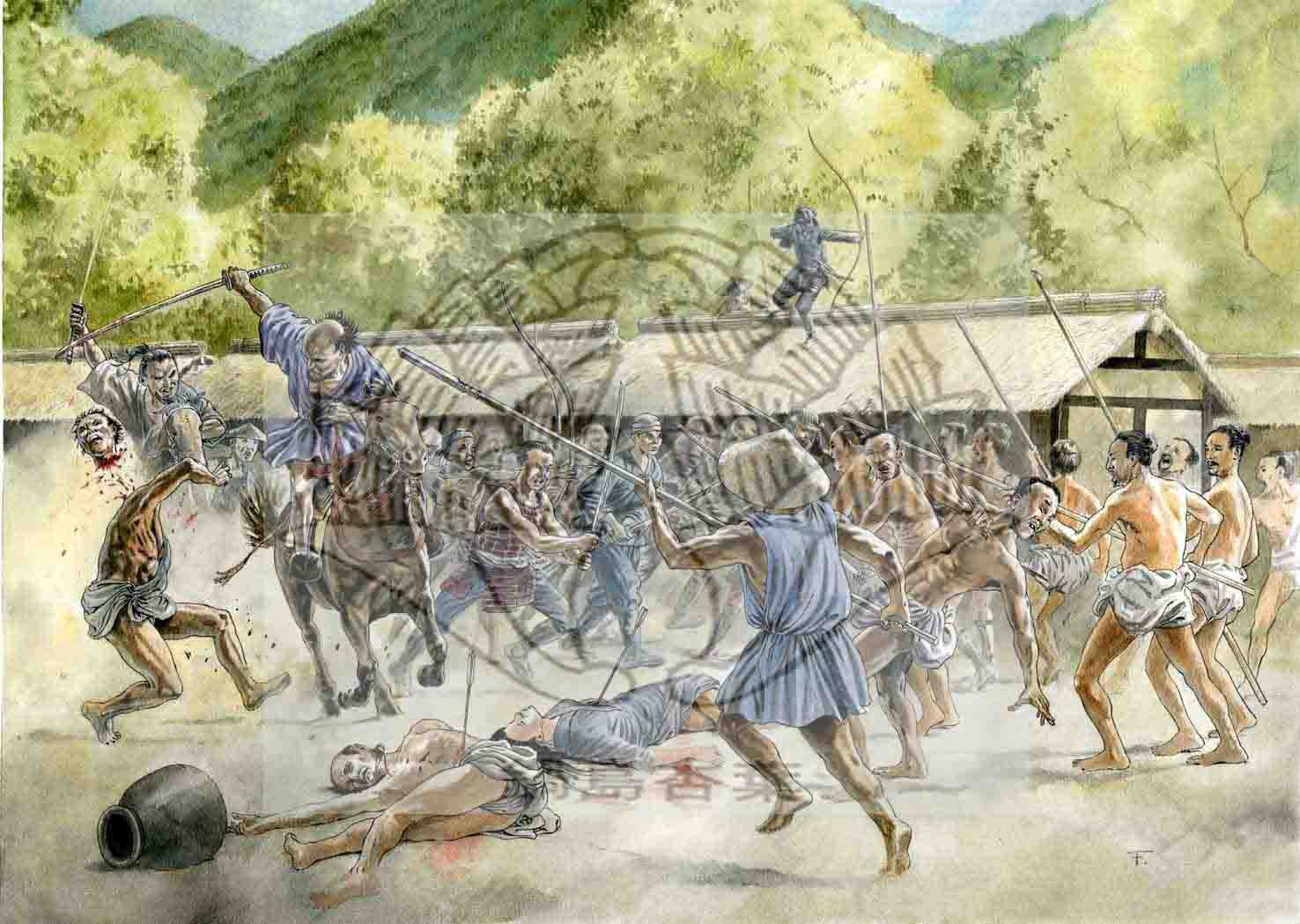

Everything went according to Ieyasu’s plans at the moment, but things would soon turn to the worse. Autumn 1563, September, all hell broke loose in and around Okazaki Castle (one source states that it took place in 1562). A large Ikkô Ikki rebellion erupted, and soon Ieyasu needed to fight for his life – in order to escape the swords of the enemy he had to hide in a small cave for a while – or so the story goes. This rebellion was certainly not expected, and soon he found out that several of his so-called “loyal retainers” had joined in with the enemy. There are several stories on the reason for this Ikkô Ikki outbreak, and one of the stories states that a retainer of the Matsudaira by the name Suganuma Sadaaki was ordered to erect a fortress on a hill at Sazaki (Okazaki City, Sazaki), and not far from the site the temple of Jôgûji. Suganuma ordered his men to go to the temple and confiscate rise from the temple’s storage. This act was naturally something the monks at the temple objected to, and soon there came to violence. This is one of the stories and there are several questions to this version – one is that there are no other information on this Suganuma Sadaaki, and some states he never existed. Well, be that as it may – one other version states that at the village of Watari, southeast of Okazaki, lays the temple of Honshôji. Close to the temple entrance there was a store, run by Torii Jôshin a Buddhist monk. One day a lot of soldiers came to his store and within a short time the store was almost leveled to the ground. Angry soldiers that owed Torii money had now rampaged the place. The monks inside the temple heard the commotion outside and soon they came armed with bô (wooden poles), and as a united force they hunted the soldier back to where they came from – some say all the way back to Okazaki Castle. Ieyasu got news of what had happened and soon armed soldiers were dispatched to quell the rebellious monks.

This was the spark that lighted the rebellion in Mikawa province. Within a short period of time many other temples and common people, and samurai, joined in with the insurgents. In just a few weeks everything had turned upside down for Ieyasu – almost at his doorstep a new enemy was knocking at his castle-gate.

The Ikkô Ikki

There was mainly 3 large temple complex that had joined forces in this uprising, the Jôgûji at Sazaki, the Honshôji at Nodera and the Shômanji at Harisaki. All of these had strong ties to the Honganji Temple, especially in the Kaga and Echizen provinces. This would be the Jôdô Shinshû sect of Buddhism. In addition to these three, was the temple of Honshûji (Zenshûji) at Toro, to the south of Okazaki.

Under Imagawa rule the Jôdô temples of Mikawa held many valuable perks, such as lower tax, more or less self-government and the “no trespassing law” – that is to say no one other than monks or people with explicit permission from the temple itself could enter the temple complex. They could also conduct several forms of business enterprises – and this self-government and freedom made the temples in question very wealthy. When Ieyasu came to power in Okazaki he needed to build and strengthen castles and provide for his soldiers better – all of these extra expenditures made it necessary to implement new taxes for all – even the temples belonging to the Jôdô sect, thereby revoke their privileges. This is considered to be an important factor to why a large rebellion broke out, and why it was connected to the temples mentioned above. To blame the Imagawa for letting the temples in Mikawa receiving a total freedom would be wrong – it was in fact Ieyasu’s father, Hirotada, that granted the rights to the temples in the first place.

The surprise of the Ikkô Ikki rebellion was one thing, but what Ieyasu did not expect was that many of his retainers would join in the uprising. Like why the rebellion started there are also many stories on why many samurai joined in with the sectarians. One reason might be the fact that after Yoshimoto’s death in 1560, many families, small and large, wanted or wished for their own family’s freedom and independence. They thought probably why should they go from one master over to another, they could just as well rule by themselves. One more factor has to be mentioned, many of the samurai were religious and they faced now a real dilemma – should they follow their oath to the Matsudaira or their oath to their faith and temple? Many faced this problem and a few experienced the change of heart during the fighting – they decided not to fight against Ieyasu. So there was a lot of confusion among the insurgents – probably on both sides. On the Ikkô side we have Matsudaira Ietsugu on Sakurai Castle (it is also recorded in some sources that he was neutral), Honda Masanobu, Hachiya Sadatsugu, Natsume Yoshinobu and the Matsudaira clan on Ôkusa Castle, among others. In addition to “loyal” vassals of the Matsudaira there were a lot of other more independent lords, high and low, that joined in the rebellion – among these; Kira Yoshiaki on Tôjô Castle, Arakawa Yoshihiro and Sakai Tadahisa (in a new source read Tadanao) on Ueno Castle. But exempt all these samurai of various rank, we find a lot of common people and many of these were lightly armed and with just a bamboo spear at hand they joined in the fighting.

The Opposing Forces

Reliable sources are sparse on the numbers involved on both sides, but on the four temples that made out the base for the rebellion one can find the following;

Honshôji at Nodera, more than 100 cavalry and many foot samurai.

Jôgûji at Sazaki, more than 100 cavalry and many foot samurai.

Shômanji at Harisaki, 118 cavalry and many foot samurai.

Honshûji at Toro, more than 120 cavalry and many foot samurai.

So, the cavalry force came to about 450, and the number for the foot samurai must surely have been more than 1000. In addition to the foot soldiers there might have been a lot of warrior monks and common people as well, many armed with just a bamboo-spear, – so the true numbers for the Ikkô Ikki side can’t be verified, but they surely were a force to be reckoned with, and Ieyasu was not at all sure about the outcome of this war.

Ieyasu on the other hand could assemble a lot of warriors of samurai rank, and although there are no exact numbers – when considering that almost all, but one of, the Matsudaira clans had joined his banner – so it must have been several thousand. In addition, there were all the clans still loyal to Ieyasu, they too joined in the fray.

The War Begins

The fighting commenced on the 5th of September 1563 and in the beginning it seems that the Ikkô Ikki made some progress, although the situation were chaotic. There is some information on battles here and there, and to some extent the main course of events can be followed. In fact Okazaki Castle was more or less surrounded by enemies, and the only thing that stood in their way was that among all the temples and enemy bastions Ieyasu had loyal lords, and these exerted good tactical operations that forced the enemies back to their base whenever they tried to move towards Okazaki, or any other place for that matter. After many weeks with this hither and thither tactic, Ieyasu finally got a break. On the 24th of October forces under the command of Matsui Tadatsugu and Matsudaira Kamechiyo attacked the castle of Tôjô, held by Kira Yoshiaki, later also Honda Hirotaka took part in the battle, and Kira was forced to surrender. With this victory one of the main leaders of the samurais was out of the game. In the end of October 1563 Ieyasu and his forces met the Ikki army at Sazaki – it ended with victory for Ieyasu. And yet again on the 25th of November – he managed to defeat an Ikkô Ikki force at Azukizaka, and at this battle a “former” Ieyasu vassal by the name of Hachiya Hannojô, renowned for his use of spear, came almost face to face with his former lord. But instead of fighting on, Hachiya lost heart and fled the field of battle – It seems that he was unable to raise his spear at Ieyasu. Then on the 7th of January there were several encounters and Ieyasu, in person, struck down a samurai by the name of Watagiri Magoshichirô. On the 11th of January 1564, the castle of Kamiwada was surrounded by an Ikki force, Ieyasu received the information and at once he set off from Okazaki to aid in the defense. Ieyasu and his force met with the enemy and a fierce battle ensued, the fighting continued for two days, but in the end Ieyasu was the strongest and forced the enemy back. On the 25th two samurais by the name of Aoyama and Fukatsu acted as shinobi (spies), and they entered the premises of Jôgûji temple and managed to set a part of the temple on fire. But the two men were discovered by the monks and killed. Not giving up, the Ikkô Ikki from Jôgûji temple ventured out again on the 13th of February, and maybe as revenge to the previous sneak attack from Ieyasu’s soldiers the target became Okazaki Castle itself. Ieyasu got news on the approaching enemy force, and instead of facing a siege, Ieyasu wanted to meet the enemy in open battle. He was personally in the front and during the fighting it is said that his armor was struck by two teppô-bullets, but since his armor was of top quality the bullets inflicted no harm to his body.

Now, the Ikkô Ikki lost the will to continue the fighting. Several crushing defeats weekend their ranks and several samurais of rank surrendered. Ieyasu was lenient towards the lords that had fought against him, and among those pardoned were Honda Masanobu, Hachiya Sadatsugu and Watanabe Masashige (or maybe read Masanari).

Some of his eager opponents fled the land; Sakai Tadahisa put his money on Ujizane and fled to Sunpu in Suruga. Kira Yoshiaki and Arakawa Yoshihiro fled towards the north – exactly where, unknown. On the matter on punishment for the temple warriors and the common people (the Ikki) that had taken part in the rebellion, Ieyasu showed great heart and he pardoned them all. In one great pardoning swoop the province of Mikawa returned to a quiet and peaceful place.

The Final Chapter

With this victory over the coalition forces of samurai, monks and common people, Ieyasu showed he had what was needed to lead and rule. There would be no more unrest within his province. But still a few remaining castles held out, they were still under Imagawa control and influence. Several of the southeastern castle-lords turned against Imagawa and joined up with Ieyasu. They had seen at firsthand what Ieyasu was capable of, and how he had defeated a rather large rebellious force right at his own doorstep.

The final opposition within Mikawa was Yoshida Castle in the southeastern part – it was located almost on top of the Tôkaidô Road, and the castle commander was a stubborn fellow and had no intention of giving up his castle without a fight. So it had to be taken by force. On the 20th of June 1564, the castle of Yoshida was attacked by Ieyasu’s forces. Its castle commander was Obara Shizuzane (Ôhara Sukeyoshi), and he was a loyal Imagawa vassal until the end. The attackers won and the castle was handed over to Ieyasu’s captain Sakai Tadatsugu.

The battle for Mikawa was now over. Over the next couple of years Ieyasu established a solid and a relatively righteous rule over the province and its people. Letters went out to various temples and samurai where their land and domains were granted and verified. At the same time samurai throughout the province had to pledge loyalty towards the Matsudaira, in fact to Ieyasu. Ieyasu placed loyal retainers in castles at strategic places. As an example was Sakai Tadatsugu granted the post as supervisor over the eastern part of Mikawa, and his base castle was to be Yoshida.

In March 1565 three of Ieyasu’s most loyal captains; Kôriki Kiyonaga (1530-1608), Honda Shigetsugu (1529-1596) and Amano Yasukage (1537-1613), were promoted to magistrates (bugyô) on civil and justice issues within Mikawa.

In December of 1566 Ieyasu was granted, by the Imperial Court, permission to change his surname from Matsudaira to Tokugawa.

All the past ill-blood that had flowed through the province seemed to be forgotten, and from now on Ieyasu and his band of vassals could turn their attention outside of their home province – and his goal is widen known.

Sources (all in Japanese)

Ieyasu den. By Nakamura Kôya. Kôdansha Tokyo 1965.

Ieyasu shiryôshû. Jinbutsu ôraisha Tokyo 1965.

Ikkô Ikki no kisô kôzô. Shingyô Norikazu. Yoshikawa Kôbunkan Tokyo 1975.

Sengoku jidai no Tokugawashi. Irimoto Masuo. Shinjinbutsu ôraisha Tokyo 1998.

Okazaki shishi chûsei 2. Okazaki 1989.

(and many more)